The Origin of Pho

Phi is generally believed to have taken shape in the early 20th century. Regarding its first appearance in Vietnam, there are two main views: one says it originated in Nam Dinh, the other claims it began in Hanoi. Both places played a key role in making this dish famous. As for its culinary origin, some believe that phở was inspired by a Cantonese dish called ngau yuk fan (in Sino-Vietnamese: “nguu nhuc phan”). Others argue that it evolved from a Vietnamese dish called xao trau (made with rice noodles), which was later transformed into xao bo (beef stew with steamed rice rolls). Another theory suggests that pho was influenced by the French beef stew pot-au-feu (pronounced “po to pho”), combined with Vietnamese herbs and spices.

Despite the many theories about its deeper origins, one thing is certain: pho originated in Northern Vietnam. It later spread to Central and Southern Vietnam around the mid-1950s, after France’s defeat in Indochina and the division of Vietnam into two regions. Northern Vietnamese migrants brought pho to the South in 1954, where it began to take on new characteristics.

Today, pho is prepared and flavored in various ways. In Vietnam, there are regional names to distinguish them: pho Bac (Northern pho), pho Hue (Central), and pho Sai Gon (Southern). Typically, Northern pho is known for its savory taste, while Southern pho is sweeter and served with more herbs. The noodles in Southern Vietnam are thinner than those in the North.

Originally, pho only came in the well-done beef version with cuts like chin, bap, nam, and gau. Later on, diners accepted rare beef (tai) and even chicken pho. Some restaurants experimented with duck or goose meat, but these versions didn’t become popular. Other dishes made from pho noodles have emerged, like pho cuon (rolled pho), pho xao (stir-fried pho, popular in the 1970s), and pho ran (fried pho, from the 1980s).

Author Thach Lam once wrote in his book Ha Noi Ba Muoi Sau Pho Phuong (Hanoi’s 36 Streets):

“Pho is a special delicacy of Hanoi. It’s not exclusive to Hanoi, but it is only in Hanoi that it tastes truly delicious.”

A good bowl of pho, he said, must be “classic,” made with beef, “the broth must be clear and flavorful, the noodles tender yet firm, the beef brisket fatty but not chewy, served with lime, chili, and onions,” and “fresh herbs, pepper, a drop of fragrant lime juice, with just a hint of ca cuong essence, barely there like a whisper.”

In the 1940s, pho was already widely popular in Hanoi:

“It was a dish for all social classes, especially office workers and laborers. People ate pho for breakfast, lunch, and dinner…”

From the mid-1960s to before the 1990s, due to economic hardship and a centrally planned food supply system, a version of pho known as pho khong nguoi lai (“pilotless pho”—i.e., pho without meat) emerged in Hanoi and across Northern Vietnam, served in state-run food stores. During the subsidy period, Hanoi locals often added a lot of monosodium glutamate (MSG) to the broth. From the 1990s onwards, with the economic reforms, pho became more varied, and Hanoians began eating pho with small pieces of fried dough (quay). In Hanoi, pho is a unique and beloved dish with an unknown origin date, typically enjoyed on its own as breakfast, lunch, or dinner—not paired with other dishes. The broth is made from simmered beef bones (knuckle, marrow, and rib bones). The meat used can be either beef or chicken. The noodles should be thin, soft, and chewy, and the garnish includes scallions, black pepper, chili vinegar, and sliced lime.

Famous Pho Restaurants

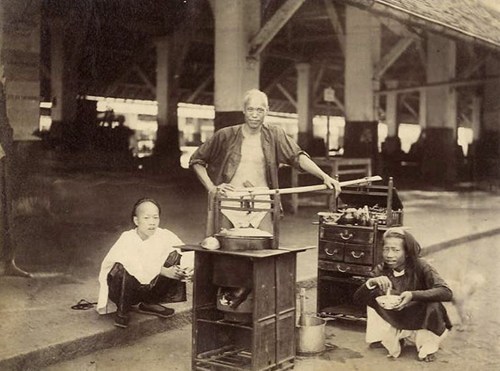

– Some pho restaurants in Hanoi have been passed down through three generations, such as: Pho Phu Xuan on Hang Da Street (originally from Phu Gia Village, Phu Thuong Ward, Tay Ho District), Pho “Bac Nam” on Hai Ba Trung Street, Pho Ga “Nam Ngu,” Pho “Thin,” Pho “So 10 Ly Quoc Su,” and Pho Bat Đan. In the past, Hanoi also had pho ganh—mobile pho vendors who carried everything on shoulder poles. One end held a container with all ingredients, bowls, chopsticks, and spoons; the other end held a pot of broth on a charcoal stove. Before 1980, these pho ganh vendors roamed Hanoi’s alleys and streets, their calls forming a part of the city’s nighttime food culture. Today, with urban development and more restaurants, these mobile vendors have become rare.

– When Northerners migrated to the South in 1954 after the Geneva Accords, they brought pho with them. In the South, especially in Saigon, pho beef cuts are typically served in five styles: chin (well-done), tai (rare), nạm (flank), gau (fatty brisket), and gan (tendon), according to customers’ preferences. A separate bowl of beef fat broth is sometimes served if requested.

– Southern pho is often accompanied by hoisin sauce, red chili sauce, lime, fresh chili, sawtooth coriander (ngo gai), Thai basil, bean sprouts, and thinly sliced onions. These garnishes are served on a separate plate or basket so customers can add what they like. Later, some shops added other herbs like ngo om, hung Lang, scallions, and more. The Southern broth usually contains no MSG like in Hanoi, and is more opaque, often sweeter and richer, sometimes made with chicken bones, dried squid, grilled onions, and ginger.

– Many famous pho restaurants in Saigon before 1975 include: Pho Cong Ly, Pho Tau Bay, Pho Tau Thuy, Pho Ba Dau, Pasteur Street (known for beef pho), and Hien Vuong Street (famous for chicken pho). Most of these restaurants still exist today, passed down to the grandchildren, though many say they’ve lost the intense flavors and charm they once had before 1975. Notable modern chains include Pho 5 Sao, Pho Quyen, Pho 2000, and Pho Hoa.

– After 1975, Saigon-style pho made its way overseas to the U.S., Australia, and Canada. In the U.S. alone, unofficial statistics from 2005 estimate that Vietnamese pho restaurants generated around $500 million in annual revenue.

Reflections on Pho

Hanoi has the highest density of phở restaurants in the country. From elegant establishments to humble roadside stalls and mobile vendors, pho can be found on nearly every street and alley in the city.

Hanoians can eat pho all day—breakfast, lunch, dinner, and even late at night. They can eat it many times a month, year after year, yet you’ll hardly ever hear a Hanoian say they’re tired of pho. And if they do, it’s only for a moment—like lovers briefly upset with each other for no reason, only to reconcile and become inseparable once more.

Hopefully, through this, everyone will gain a deeper appreciation for pho, especially beef pho—a humble, simple dish that’s rich in traditional Vietnamese cultural identity. So that each time we savor a bowl of pho, we feel the soul of Vietnam infused in its taste, and that soul may rise and travel far, yet always remember its roots in the motherland, Vietnam.